What is Dravet Syndrome?

Dravet syndrome is an intractable developmental and epileptic encephalopathy that begins in infancy and proceeds with accumulating symptom burden that significantly impacts individuals throughout their lifetime. Dravet syndrome is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence of 1:15,700. The majority of patients carry a mutation in the sodium channel gene SCN1A.

What is Dravet syndrome?

Dravet Syndrome is More than Seizures

Dravet syndrome, previously known as Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy of Infancy (SMEI), is a medication-resistant developmental and epileptic encephalopathy that begins in infancy and proceeds with accumulating symptom burden that significantly impacts individuals throughout their lifetime. Dravet syndrome is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence rate of 1:15,700, with the majority of patients carrying a mutation in the sodium channel gene SCN1A [1].

Dravet syndrome is classified as a developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (also known as a DEE). DEEs are a group of severe epilepsies with frequent and difficult to treat seizures and significant developmental delays. Seizures in Dravet syndrome usually begin during the first 2-15 months of life, often in the presence of fever or warm temperatures. Seizures are frequently prolonged, and are not well managed with current medications. Patients present with a variety of seizure types that generally evolve with age. As with all developmental and epileptic encephalopathies, Dravet syndrome includes more than just difficult to control seizures. Other comorbidities such as developmental delay and abnormal EEGs often emerge during the second or third year of life. Common issues associated with Dravet syndrome include:

- Prolonged seizures

- Frequent seizures

- Behavioral and developmental delays

- Movement and balance issues

- Orthopedic conditions

- Delayed language and speech issues

- Growth and nutrition issues

- Sleeping difficulties

- Chronic infections

- Sensory integration disorders

- Dysautonomia, or disruptions of the autonomic nervous system which can lead to difficulty regulating body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and other issues

Current treatment options are limited, and the constant care required for someone suffering from Dravet syndrome can severely impact the patient’s and the family’s quality of life. Patients with Dravet syndrome face a 15-20% mortality rate due to SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy), prolonged seizures, seizure-related accidents such as drowning, and infections [2,3].

Research for improved treatments, particularly disease-modifying treatments, offers patients and families hope for a better quality of life for their loved one. Earlier diagnosis, expert treatment guidelines, newer antiseizure medications, and clinical studies for gene-targeted therapies are all improving the future outlook for patients with Dravet syndrome.

Diagnosis & Genetic Testing

DIAGNOSIS

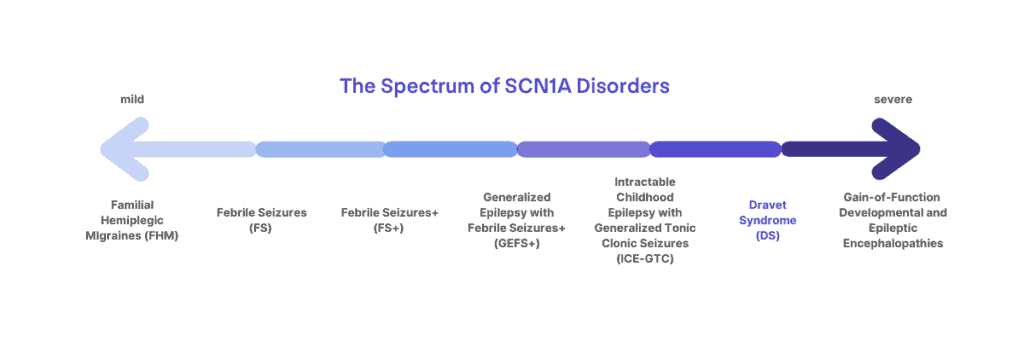

Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis that affects 1:15,700 infants born in the US [1]. Over 90% of those diagnosed with Dravet syndrome have an SCN1A mutation, but the presence of a mutation alone is not sufficient for diagnosis, nor does the absence of a mutation exclude the diagnosis. Mutations in SCN1A can lead to a spectrum of disorders ranging from migraines, childhood epilepsy, or more severe and life-long epilepsy syndromes. Dravet syndrome lies at the more severe end of the spectrum of SCN1A-related disorders. Dravet syndrome can more rarely be associated with mutations in genes other than SCN1A [4,5].

Clinical diagnostic criteria include at least 4 of the following:

- Normal or near-normal cognitive and motor development before seizure onset

- Two or more seizures with or without fever before 1 year of age

- Seizure history consisting of myoclonic, hemiclonic, or generalized tonic-clonic seizures

- Two or more seizures lasting longer than 10 minutes

- Failure to respond to first-line antiepileptic drug therapy with continued seizures after 2 years of age

Other earmarks of the syndrome include seizures associated with vaccinations, fever, hot baths, or warm temperatures; developmental slowing, stagnation, or regression after the first year of life; behavioral issues; and speech delay.

GENETIC TESTING

Because many of these criteria are not apparent in the first year of life and infants with Dravet syndrome initially experience typical development, genetic testing via an epilepsy panel should be considered in patients exhibiting any of the following:

- 2 or more prolonged seizures by 1 year of age

- 1 prolonged seizure and any hemi-clonic (sustained, rhythmic jerking of one side of the body) seizure by 1 year of age

- 2 seizures of any length that seem to affect alternating sides of the body

- History of seizures prior to 18 months of age and later emergence of myoclonic and/or absence seizures

If you suspect your loved one might have Dravet syndrome, ask your neurologist about testing, which is available through your doctor or commercially. An epilepsy panel will test for SCN1A as well as many other genes commonly associated with epilepsy. Following testing, consultation with a genetic counselor is recommended. Genetic testing is recommended in patients of ALL ages, including in adults with a suspected diagnosis but for whom a detailed history of presentation in infancy may be limited. While simple SCN1A sequencing is appropriate when all clinical criteria are met, an epilepsy gene panel or broader sequencing is the expert preference for children with suspected Dravet syndrome.

- Invitae’s Unlock Epilepsy Program provides genetic testing for children under 18, in the U.S., who have experienced an unprovoked seizure. It is designed to ensure access for patients whose insurance does not cover genetic testing or who do not meet their payer’s eligibility requirements. at least one unprovoked seizure.

- Probably Genetic offers no-cost genetic testing (whole exome sequencing) for pediatric-onset epilepsy.

- GeneDx has an Epilepsy Partnership Program that can help with access to exome sequencing for patients under 18 years of age who have not yet received a genetic diagnosis.

Dravet syndrome presents differently in each patient. Individuals with Dravet syndrome are often misdiagnosed with another seizure disorder such as Lennox Gastaut or Myoclonic Astatic Epilepsy, or given a broad diagnosis of intractable epilepsy. Some epilepsy syndromes, like PCDH19, a rare x-linked epilepsy found more often in females than males, share many characteristics with Dravet syndrome. There are subtle differences between these epilepsy syndromes and Dravet, and you should consult with your child’s neurologist if you have any questions about related epilepsies.

Genetic Testing and Diagnosis: What does an SCN1A result mean?

If your infant or young child just received a genetic test result indicating an SCN1A mutation, you may still be unsure about what that means for a clinical diagnosis and their long-term outcomes. Patients are gaining access to genetic testing earlier than ever before- which is amazing for improving access to the correct treatments and specialists earlier! However, this means that many patients are receiving a genetic result prior to typical age of onset of many of the symptoms of Dravet syndrome (such as developmental delays).

Whether a patient receives a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome following an SCN1A result on their genetic report may depend on the patient and their symptoms, the specific mutation(s) on the report, and the treating clinician’s approach. As shown above, there are a spectrum of disorders associated with SCN1A mutations, several of which include epilepsy. Genetic testing can help to guide diagnosis, but it must be considered in the context of clinical symptoms. For example, two patients might carry the exact same mutation and still have different diagnoses, such as Dravet syndrome and GEFS+. Additionally, even within the diagnosis of Dravet syndrome, there can be a lot of variability in when and to what extent symptoms present. Published studies of the patient population can report common trends, but there are outliers and a lot of variability.

Regardless of the long-term outcomes, an earlier identification of an SCN1A mutation in a child with epilepsy can help patients and their families receive the most appropriate medications and ensure that they have access to information and resources about Dravet syndrome and other SCN1A-related disorders.

Read more about the GENETICS OF DRAVET SYNDROME

Frequently Asked about Dravet Syndrome

What is Dravet syndrome?

Dravet syndrome is a rare form of intractable epilepsy that begins in infancy and proceeds with accumulating morbidity that significantly impacts individuals throughout their lifetime.

Dravet syndrome is part of a group of severe epilepsies that are referred to as Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies (DEEs). DEEs are characterized by frequent and usually very difficult to treat seizures as well as significant developmental delays.

Is Dravet syndrome a rare disease?

Dravet syndrome is a rare disease with an estimated incidence rate of 1:15,700 individuals.

How do you pronounce Dravet syndrome?

Dravet is pronounced “dra-vay”

How is Dravet syndrome diagnosed?

Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based upon the presentation of symptoms, including often-prolonged refractory seizures during the first year of life in an otherwise typically developing child. A clinical diagnosis means that a doctor diagnoses the syndrome based on the symptoms they observe in a clinical work-up. Results from genetic testing, while not required, can help to confirm the diagnosis. In the majority of cases, Dravet syndrome is caused by a mutation in the gene SCN1A. SCN1A codes for a protein called Nav1.1, which is a sodium channel important for neurons in the brain to communicate effectively. Mutations in SCN1A that cause Dravet syndrome result in a 50% reduction in the number of properly functioning Nav1.1 sodium channels. This reduction, called a haploinsufficiency, disrupts the normal pattern of brain communication, leading to symptoms like seizures.

Is Dravet syndrome inherited?

In 90% of cases, Dravet syndrome is not found to be inherited from parents, but rather caused by a “de novo” (or new) mutation. There are some situations where a parent may carry a mutation without presenting with Dravet syndrome, and thus have a 50% chance of passing the gene mutation on to their children. This could occur due to a phenomenon known as “mosaicism,” where only some cell populations in an individual carry the mutation. There also appear to be other processes that contribute to the “penetrance” of a mutation, meaning that individuals carrying the same SCN1A mutation may have a different presentation of signs and symptoms. In these cases, a parent or family member may have the same mutation in SCN1A, but they did not experience symptoms or experienced much milder symptoms.

Can you “outgrow” Dravet syndrome?

No, Dravet syndrome is a life-long disorder caused by a genetic mutation in the SCN1A gene. The majority of patients continue to experience seizures and other accumulating comorbid conditions into adulthood, and all patients will depend on caregiving assistance throughout their life.

Are there different types of Dravet syndrome?

There is only a single diagnosis for Dravet syndrome, although the signs and symptoms can all present differently from patient to patient with a lot of variation in severity. However, mutations in the SCN1A gene do not all cause Dravet syndrome, and can result in a spectrum of diagnoses that include migraine disorders and less severe epilepsy syndromes like Generalized Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures + (GEFS+). Sometimes understanding where the mutation occurs in the SCN1A gene can help to determine a more precise diagnosis when combined with a clinical assessment, but it can still be difficult in very young children to distinguish between Dravet syndrome and GEFS+ until they age and symptoms become more (or less) apparent. Some very young patients may not get a clear diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are a bit older, and even then, it is not possible to predict how severe the symptoms may be from one patient to another.

How does Dravet syndrome present?

Initial seizures are often triggered by fever, warm temperatures or baths, illness, or vaccinations, but can also onset without any known trigger. Seizures may present on one side of the body (focal) or impact the entire body (generalized). Seizures in individuals with Dravet syndrome are generally difficult to control with medication, and early seizures are often prolonged. As children age, they may experience new seizure types and triggers as well as many other comorbidities that may include: behavioral and developmental delays, movement and balance issues, orthopedic conditions, delayed language and speech issues, growth and nutrition issues, sleeping difficulties, chronic infections, sensory integration disorders, and dysautonomia.

How is Dravet syndrome diagnosed?

Dravet syndrome is diagnosed based upon the clinical presentation. This generally includes often prolonged, frequently febrile, seizures during the first year of life in an otherwise typically developing child. Genetic testing can help to confirm the clinical diagnosis, as over 85% of individuals with Dravet syndrome have a causal mutation in the SCN1A gene. Sometimes, it may be difficult to determine the diagnosis in a very young child as mutations in the SCN1A gene can cause several seizure disorders that vary in severity and presentation of comorbidities.

Is Dravet syndrome progressive?

The signs, symptoms, and comorbidities of Dravet syndrome may change over time. While development generally occurs normally during the first year of life, delays and impairments are often observed by the time children reach school age that affect cognition, behavior, motor development, sleep, and language skills. Seizure types, frequency, and duration may vary with age. Motor deficits that begin in childhood may progress during adult years.

Can my child’s genetic diagnosis predict their long-term outcomes?

Unfortunately the results of genetic testing can not predict how severe the presentation of symptoms may be for a patient. Genetic diagnosis alone is still not always enough to determine whether a patient will have Dravet syndrome versus GEFS+, let alone how severe their symptoms may present within those diagnoses. There may be many factors that contribute to the long-term outcomes, including the rest of their genetics, medications (such as use of contraindicated sodium channel blockers), or other impacts from environmental factors.

My child was just diagnosed with Dravet syndrome. Now what?

We know receiving a new diagnosis can be overwhelming, and DSF is here to help. Begin by registering for our Family Network to stay connected and gain access to support tools, such as our Newly Diagnosed Patient Kit. DSF also has a downloadable Newly Diagnosed Checklist to help you get organized. Connecting with other families also navigating life with Dravet syndrome can be an incredible support and you can learn from their wealth of lived experience. DSF moderates Facebook Support Groups for parents and primary caregivers of patients living with Dravet syndrome.

Can Dravet syndrome be cured?

There is no cure for Dravet syndrome. Dravet syndrome is caused by an underlying gene mutation that disrupts the way the cells in the brain communicate. To truly cure Dravet syndrome, you would need to correct this gene mutation in the DNA of every cell that needs the SCN1A-Nav1.1 sodium channel. However, there are many different efforts underway by both academic research labs and biotechnology/pharmaceutical companies to better address this underlying issue and treat the root cause of Dravet syndrome. Therapies that compensate for the SCN1A gene mutation directly may be able to truly modify the disease and treat more than just the seizures. Some genetic-based therapies for Dravet syndrome are currently being tested in human clinical trials (as of June 2024).

Is there a gene therapy for Dravet syndrome?

There are many researchers working on different approaches to gene therapy to correct the underlying cause of Dravet syndrome- mutations in the SCN1A gene that reduce expression of the Nav1.1 sodium channel. As of June 2024 two genetic-based therapies are currently in human studies for Dravet syndrome. An antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) developed by Stoke Therapeutics called STK-001 has completed Phase 1/2a human trials (which began in August 2020) with initial results showing positive impacts on seizures and some measures of cognition and development. Stoke Therapeutics is working towards a global Phase 3 trial for STK-001. An AAV-delivered gene regulation therapy called ETX101 developed by Encoded Therapeutics received approvals to begin human studies in the US, UK, and AUS in early 2024 and are currently enrolling patients. You can read more about gene therapies in development for DS here: https://dravetfoundation.org/dsf-funded-research/gene-therapy-for-dravet-syndrome/

What is the life expectancy of a child with Dravet syndrome? / Is Dravet syndrome fatal?

The majority of individuals with Dravet syndrome (80% or more) reach adulthood. Patients with Dravet syndrome face a 15-20% mortality rate due to Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP), prolonged seizures, seizure-related accidents such as drowning, and infections.

Will my child with Dravet syndrome ever live independently?

Currently, all patients with Dravet syndrome will need some form of caregiver support for their entire life. The severity of symptoms and required support for daily tasks can vary from one patient to another. As treatments for Dravet syndrome continue to improve and disease modifying therapies become a reality, there is much hope for improved long-term outcomes for patients.

Are there any research studies I can participate in?

You can find actively enrolling research studies for Dravet syndrome curated by DSF at this page, or by visiting clinicaltrials.gov.

What resources does DSF offer to families affected by Dravet syndrome?

DSF provides educational resources, connection, advocacy, and financial support to families affected by DS. Our website houses educational resources including written guides and webinar recordings covering the latest in research, clinical care, and daily living. Registering with DSF’s Family Network keeps caregivers connected to the latest events as well as providing access to moderated Facebook support groups. DSF can help empower families to advocate and fundraise for research for better treatments for DS. Additionally, DSF has Patient Assistance Programs that can provide financial support for purchases related to patient medical needs or other unique situations.

How can I meet other families affected by DS?

DSF can help you connect with other patient families in a variety of ways. After registering with the DSF Family Network, parents and primary caregivers can join our moderated Facebook support groups to connect with families from around the world. Our Parent Ambassadors are available for questions and guidance on resources and programs. Attend our in-person educational events such as the DSF Biennial Family & Professional Conference and regional Day of Dravet workshops. Our Caregiver Connect Grants provide financial support for families to plan local gatherings. Be sure to watch for fundraising events in your area through our newsletter or website.

What is the DSF Biennial Conference?

The DSF Biennial Conference is a 3-day event that brings together patient-families, clinicians, researchers, and professionals in the pharmaceutical industry providing a unique opportunity for connection and collaboration. Presentations at the conference span the latest advances in research, up-to-date information impacting patient care, and sessions specifically tailored to address the spectrum of patient-family needs.

What is the DSF Research Roundtable?

The DSF Research Roundtable is an annual meeting held at the American Epilepsy Society (AES) Conference, that brings together researchers, geneticists, neurologists and other professionals with strong interest in DS and related epilepsies. The meeting includes presentations detailing some of the most recent advancements in DS research, often from DSF-funded projects. Each year, presentations and discussions with the consortium of experts at the roundtable help DSF to establish a ‘research roadmap’ to prioritize research needs that offer the most promising breakthroughs.

I am a researcher interested in studying Dravet syndrome - how can I get involved?

DSF offers several opportunities for researchers to become more involved.

- DSF funds 4 types of research grants for independent investigators (scientists and clinician researchers) and trainees (post doctoral and clinical fellows). Contact our Scientific Director, Veronica Hood, PhD, with questions: veronica@dravetfoundation.org

- DSF hosts a Research Roundtable prior to the American Epilepsy Society (AES) Annual Meeting each year with talks and discussion surrounding cutting-edge research related to Dravet syndrome.

- DSF hosts a biennial Patient and Professional Conference to bring together patient families, clinicians, researchers, and industry for sessions on the relevant topics and recent advancements in clinical care and research related to Dravet syndrome.

I’m a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare professional looking for more information - where should I start?

DSF curates information specifically for health care providers and other medical professionals. Start out on our HCP Resource Page for the basics of Dravet syndrome in pediatric or adult patients and links to more specific content, like an overview of expert Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines. Need more information? Contact DSF’s Scientific Director.

What is the ICD-10 code for Dravet syndrome?

- G40.83 Dravet syndrome

Polymorphic epilepsy in infancy (PMEI)

Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI) - G40.833 Dravet syndrome, intractable, with status epilepticus

- G40.834 Dravet syndrome, intractable, without status epilepticus

References

- Wu, E., et. al. (2015). Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population. Pediatrics 136(5): 1310-e1315. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1807. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4621800/

- Cooper, M.S., et. al. (2016). Mortality in Dravet Syndrome. Epilepsy Research Oct 26;128:42-47. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.10.006.

- Skluzacek, et. al. (2011). Dravet syndrome and parent associations: The IDEA League experience with comorbid conditions, mortality, management, adaptation, and grief. Epilepsia Apr;52 Suppl 2:95-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03012.x.

- Ian O Miller, MD, Marcio A Sotero de Menezes, MD. SCN1A-Related Seizure Disorders. Gene Reviews. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. Seattle (WA):University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2016.

- Silberstein, S.D., Dodick, D.W. (2013). Migraine genetics: Part II.2013 Sep;53(8):1218-29. doi: 10.1111/head.12169. Epub 2013 Aug 6.